American culture has developed a curious habit of turning ordinary life into pathology.

Shyness becomes social anxiety. Stress is labeled trauma. Sadness is quickly upgraded to depression.

And now — right in time for Valentine’s Day — being single has joined the list. Being single isn’t a diagnosis. It’s just a relationship status.

Single people are often treated as if they’re suffering from a condition that requires attention.

Friends worry. Family members whisper. Acquaintances try to help.

The media inundate them with “advice” and “dating tips” in the leadup to Feb. 14 — even countless “Singles’ survival guides to Valentine’s Day.”

There are books, experts, podcasts, dating shows and entire industries devoted to fixing what is assumed to be broken.

Except nothing is broken.

Being single is not a disorder. It is not evidence of emotional deficiency.

Yet the assumptions come fast. If someone remains single long enough, curiosity turns into concern.

The question quietly shifts from “Are you happy?” to “What’s wrong?”

We would never think to ask married people why they’re married.

But asking single people why they’re single has become socially acceptable, often disguised as concern.

Singlehood is no longer treated as a neutral life circumstance. It’s seen as temporary at best and suspicious at worst.

The longer it lasts, the more pressure builds to interpret it psychologically. Normal delays get recast as internal flaws.

This shift is usually framed as empathy. In reality, it reflects a deeper discomfort with uncertainty.

Lives that don’t unfold on schedule make people uneasy. What once passed as timing now demands scrutiny.

None of this denies the value of romantic partnership.

Marriage, family and long-term commitment matter. They offer companionship, stability and love.

But valuing relationships doesn’t require treating those without them as problems in need of solving.

In my clinical work, I see how subtly this mindset takes hold.

One client told me she’d been offered four setups in two months. Each gesture was well-intentioned. Taken together, they sent a message she couldn’t ignore: Her single status itself had become a cause for concern.

That reaction says less about her than about the culture around her.

Singlehood doesn’t operate on a timetable. It can’t be optimized, scheduled or guaranteed.

In a society obsessed with outcomes and efficiency, any life that resists easy measurement starts to look like failure.

The pressure is often justified using the language of mental health. But the result is frequently the opposite.

Not every unmet desire is a mental-health problem.

When psychological language becomes the default way we interpret everyday life, it quietly reshapes how people see themselves.

Ordinary longing turns into deficiency. Normal timelines become evidence of failure.

Instead of viewing adulthood as something that unfolds naturally, people begin to monitor themselves for what they lack.

This mindset doesn’t produce growth. It produces anxiety.

People stop asking how to build fulfilling lives in the present and start obsessing over whether they are falling behind.

Comparison replaces confidence. Self-trust erodes. Life becomes something to justify rather than live.

In that environment, even contentment can feel suspicious.

A single person who is stable, productive and emotionally healthy is still treated as unfinished.

Happiness is discounted because it doesn’t conform to expectation.

The message is subtle but powerful: Fulfillment only counts if it follows the approved order.

That isn’t mental health. Instead, it’s social pressure wearing therapeutic language.

Some situations genuinely warrant intervention. Addiction. Serious mental illness. Chronic instability. Self-destructive behavior.

These are real problems. But being single is not one of them.

For some, it’s a choice. For others, a phase. For many, simply where life happens to be at a given moment.

A healthier culture would resist the urge to interpret every unmet desire as evidence of psychological failure.

Not every delay needs an explanation. Not every discomfort signals damage.

And not every adult life must follow the same script to be considered successful.

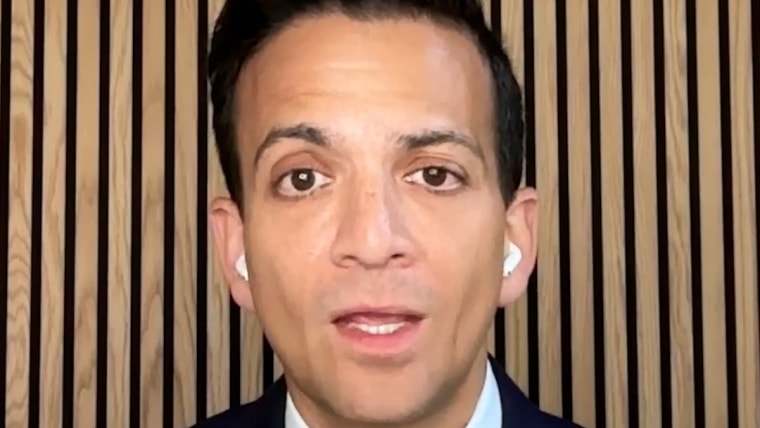

Jonathan Alpert is a psychotherapist in New York City and Washington, DC, and author of the forthcoming book “Therapy Nation.”

X: @JonathanAlpert