The shutdown of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting doesn’t mean the end of public radio and television in America, but it does mean major changes are on the way.

The government-authorized corporation announced Aug. 1 it will begin to wind down its operations after Congress rescinded about $1.1 billion of its funding. The CPB is a private nonprofit corporation that helps fund public television and radio programming, as well as about 1,500 locally managed radio and TV stations across the United States.

While known for funding popular programming from “Sesame Street” to Ken Burns documentaries, and intended to be nonpartisan, the CPB has long faced conservative critics alleging that it has a liberal bias. When Republicans gained unified control of Congress this year, President Donald Trump pushed for the elimination of the CPB’s funding.

Why We Wrote This

Congress founded the Corporation for Public Broadcasting in 1967 with the goal of providing noncommercial, educational, and accessible programming. But Republican lawmakers rescinded funding, alleging a liberal bias. The CPB’s imminent shutdown resets key aspects of the U.S. media landscape.

However, the CPB shutdown is expected to have a greater impact on stations that serve local communities than on PBS and NPR.

What does this mean for PBS, NPR, and local stations?

Congress founded the CPB in 1967 with the goal of supporting noncommercial, educational, and accessible broadcasting. Through taxpayer support, it has provided about 15% of funding for the Public Broadcasting Service, and 1% of the funding for NPR – plus the money that flows indirectly through its support of local stations, which in turn help pay for programming.

PBS is a nonprofit organization that distributes programming to its member stations. The programs it helps support have ranged from cultural touchstones like “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” to the recent popular reboot “All Creatures Great and Small.”

In the days after the CPB made its announcement, PBS News Hour posted on the social platform X that “PBS News is not going anywhere,” adding, “We will continue our work without fear or favor.”

However, while PBS’ programming may continue (including “Sesame Street,” now available on Netflix as well as PBS), the funding squeeze is real. And shows may become less widely available if smaller PBS affiliate stations struggle to replace the funding they received from the federal government.

The vast majority of the CPB’s funds – about 70% – go directly to local TV and radio stations. The degree to which these stations depend on federal support can vary considerably, with stations that serve rural communities generally being the most vulnerable to funding cuts.

A study by the Public Media Co., an advisory firm, found that 78 radio stations and 37 TV stations across the country receive more than 30% of their funding from the CPB, putting them at risk of going dark now that this funding is shutting off. Most of them serve rural areas.

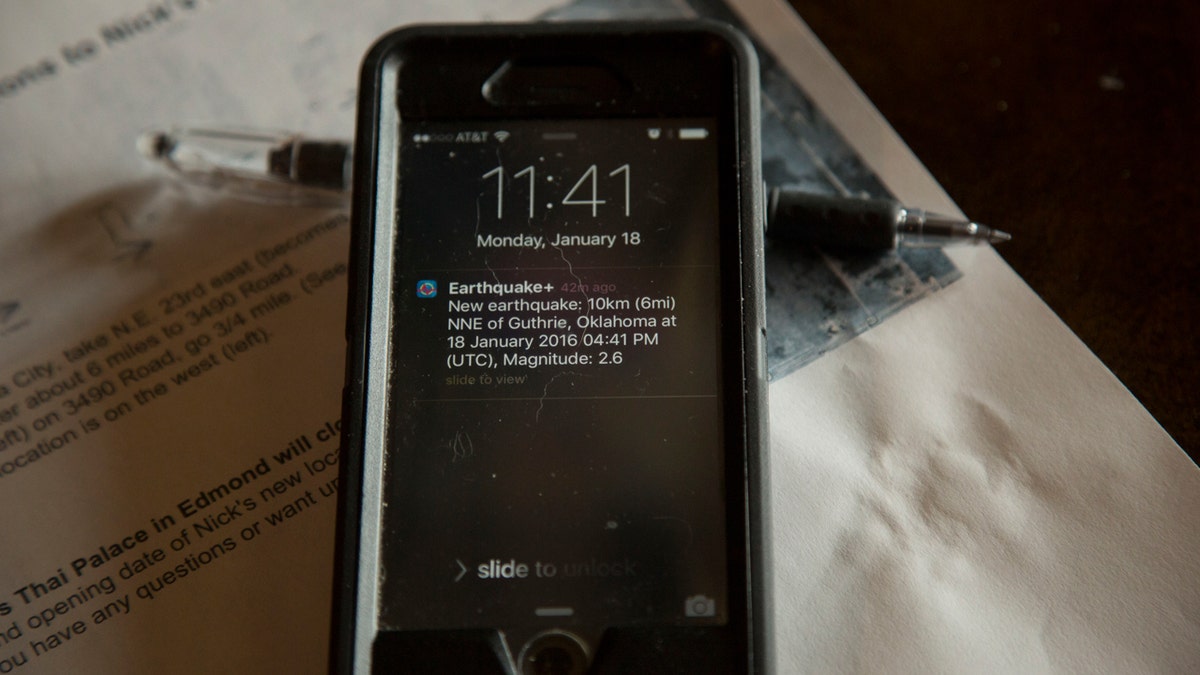

These stations often tailor their content to meet community needs, including covering local news and issuing emergency alerts for natural disasters in the area. Many local radio stations are NPR affiliates and pay dues to be able to broadcast NPR programming.

In the days since the CPB lost its funding, public radio listeners and public television viewers have mobilized to deliver an outpouring of donations. But for the stations that most rely on federal funding, the future is still uncertain.

Tom Davidson, a media professor at Pennsylvania State University, says he worries the country will end up with a “patchwork system where some cities, some communities, some markets are just fine, and others are completely bereft.”

What happens to the CPB’s remaining funds?

Congress has historically provided the CPB with funds on a yearly basis. But in July, congressional Republicans spearheaded the passage of a rescissions bill that clawed back about $1.1 billion in money that had already been approved for the CPB’s next two fiscal years. Shortly after the bill was passed, the Senate advanced an appropriations bill that didn’t include any funding for the CPB, deepening its financial straits.

The CPB awards most of its funding to local stations through community service grants, which generally give stations broad leeway to choose how the money is spent. All of those grants have already been given out for this fiscal year, which ends Sept. 30.

However, the CPB has also given out grants for specific purposes, like music license agreements or funds to update stations’ infrastructure. Those grants can last up to two years, and the money hasn’t all been disbursed – leaving many stations in the lurch.

A CPB spokesperson said the corporation is developing a plan to see if it has money to carry forward some of these existing grants.

What does this mean for emergency alerts?

Local TV and radio stations often play a critical role in alerting communities about natural disasters. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) can send emergency alerts directly to certain stations, which relay that same message to other stations in the affected area.

FEMA has other ways of disseminating warnings, such as through messages sent to people’s cellphones. But radio stations can cover a larger geographical area than a cell tower can. In rural areas where communities lack reliable internet, radio can sometimes be people’s best means of receiving these warnings. If stations are forced to shutter operations, that could leave affected communities with one fewer way to receive emergency information.

Some stations may also lose money they had received to maintain the infrastructure that allowed for these alerts. In 2022, Congress set aside money for FEMA to give to the CPB, which then distributed that money to stations to help upgrade their emergency alert infrastructure. This included projects such as upgrading radio stations’ digital capabilities to ensure they’re equipped to broadcast FEMA’s alerts, and to ensure warnings could reach people with disabilities or who speak limited English.

Tami Graham, executive director of KSUT Public Radio in Colorado, had landed a grant in February through this program to update the station’s aging infrastructure. The grant was supposed to last two years, and be paid out to KSUT in the form of reimbursements.

However, after Congress passed the rescissions package to claw back funding for public broadcasting, the CPB informed Ms. Graham that the station will have to spend any of those funds before Sept. 30. Given the current climate, she’s not sure the station can count on being reimbursed for its expenses.